How South Africa’s oldest Quran was saved by Cape Town Muslims

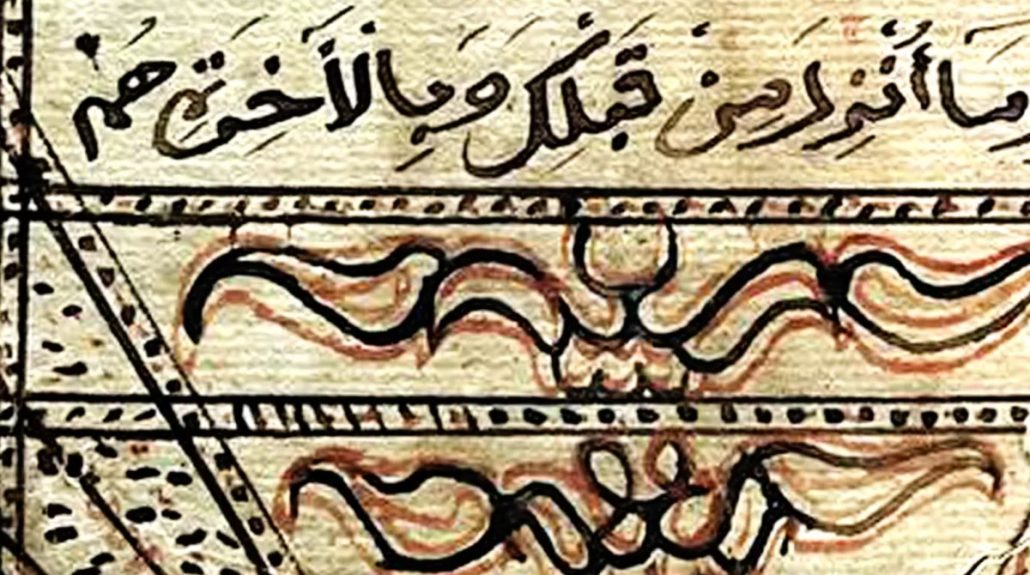

A Quran – neatly handwritten more than 200 years ago by an Indonesian imam who had been banished to the southern tip of Africa by Dutch colonisers – is the pride of Cape Town Muslims who jealously guard it at a mosque in the city’s historic Bo Kaap district.

Builders found it in a paper bag in the Auwal Mosque’s attic, while they were breaking it down as part of renovations in the mid-1980s.

Researchers believe that Imam Abdullah ibn Qadi Abdus Salaam, affectionately known as Tuan Guru, or Master Teacher, wrote the Quran from memory at some point after he was shipped to Cape Town as a political prisoner, from Tidore island in Indonesia in 1780, as punishment for joining the resistance movement against Dutch colonisers.

“It was extremely dusty, it looked like no-one had been in that attic for more than 100 years,” Cassiem Abdullah, a member of the mosque committee, tells the BBC.

“The builders also found a box of religious texts written by Tuan Guru.”

The unbound Quran, comprising loose pages that were unnumbered, was in surprisingly good condition, with the exception of the first few pages that were frayed at the edges.

The black and red ink used for the clearly legible calligraphic writing in Arabic script was, and still is, in very good condition.

The big challenge for the local Muslim community in their quest to preserve one of the most valuable artefacts in their rich heritage, which dates back to 1694, was to ensure that all the pages containing the Quran’s more than 6,000 verses were placed in the correct sequence.

This task was undertaken by the late Maulana Taha Karaan, who was head jurist of the Cape Town-based Muslim Judicial Council, in conjunction with several local Quranic scholars. The entire process, which concluded with binding the pages, took three years to complete.

The Quran has since been displayed in the Auwal Mosque, which was established by Tuan Guru in 1794 as the first mosque in what is now South Africa.

Three unsuccessful attempts to steal the priceless text prompted the committee to secure it in a fire- and bullet-proof casing in the front of the mosque 10 years ago.

Tuan Guru’s biographer, Shafiq Morton, believes that the scholar in all likelihood started writing the first of five copies while being held on Robben Island – where anti-apartheid icon Nelson Mandela was also imprisoned from the 1960s to the 1980s – and continued doing so after his release.

Tuan Guru also penned a 613-page Arabic textbook entitled Ma’rifat wal Iman wal Islam (The Knowledge of Faith and Religion) from memory.

The book, a basic guide to Islamic beliefs, was used for more than 100 years to teach the Muslims of Cape Town about their faith.

It is still in good condition and is in the possession of the Rakiep family, descendants of Tuan Guru. A replica is kept in the national library in Cape Town.

“He sat down and wrote down just about everything he could remember about his faith and he used that as a text for teaching others,” says Shaykh Owaisi.

Of the five copies of the Quran handwritten by Tuan Guru, three can still be accounted for. Apart from the one in the Auwal mosque, the other two are in the possession of his family, including his great-great granddaughter.

About 100 replicas have been produced. In April a one of them was handed over to the library of the al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem – the third holiest site in Islam – while a few have been handed over to visiting dignitaries.

In May 2019 Ganief Hendricks, leader a Muslim political party in South Africa, Al Jama’ah, used one of the replicas to be sworn in as member of parliament.

Little did the Dutch realise that by banishing Tuan Guru to southern Africa they would inadvertently be the catalyst for spreading Islam to this part of the world, where Muslims now make up around 5% of Cape Town’s estimated population of 4.6 million.

“When he came to the Cape, Tuan Guru observed that Islam was in pretty bad shape so he had a lot of work to do,” Mr Morton says.

“The community didn’t really have their hands on any texts – they were Muslims more from cultural memory than anything else.

“I would say that that first Quran he wrote is the reason why the Muslim community survived and developed into the respected community we have today.”

Most of these copies are believed to have been written when he was between 80 and 90 years old, and his achievement is seen as all the more remarkable as Arabic was not his first language.

According to Mr Morton, Tuan Guru was jailed on Robben Island twice – first from 1780 to 1781 when he was 69 years old, and again between 1786 and 1791.

“I believe one of the reasons he wrote the Quran was to lift the spirits of the slaves around him. He realised that if he were to write a copy of the Quran he could educate his people from it and teach them dignity at the same time,” Mr Morton says.

“If you go to the archives and look at the paper that the Dutch used it’s very similar to that used by Tuan Guru. It’s probably the same paper.

“His pens he would have made himself from bamboo and the black and red ink would have been easy to obtain from the colonial authorities.”

Shaykh Owaisi, a lecturer in South African Islamic history who has done extensive research on handwritten Qurans in Cape Town, believes Tuan Guru was motivated by the need to preserve Islam among Muslim prisoners and slaves in what was then a Dutch colony.

“While they were preaching the Bible and trying to convert the Muslim slaves, Tuan Guru was writing the copies of the Quran, teaching it to the children and getting them to memorise it.

“It tells a story of resilience and perseverance. It shows the level of education of the people that were brought to Cape Town as slaves and prisoners.”

2023

1,582 views

views

0

comments