‘Mirror on the Veil’: Anthology that Counters Hijabi Stereotypes

I have worn the hijab for the last decade, perhaps more. It’s difficult to count the years because it didn’t happen in one day or even a few months so that I could look back and remind myself: “there, that’s the year I finally did it!” For me, like for millions of other Muslim women, putting on the hijab was a long-term experiment, an on-again-off-again relationship with a piece of fabric.

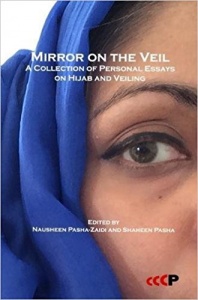

I write about this relationship in-depth in the new essay anthology “Mirror on the Veil.” Edited by two brilliant Muslim American women: Nausheen Pasha-Zaidi who is a psychology lecturer at the University of Houston and Shaheen Pasha who is a journalism professor at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst. This anthology is subtitled ‘A Collection of Personal Essays on Hijab and Veiling.’ The book is about the hijab, but not only from the perspective of those who wear it, like me, but also from the viewpoint of those who don’t wear it and those who used to but have now forsaken it.

When I contributed to the anthology I didn’t know the editors or the other contributors. After email correspondence with Pasha-Zaidi, we realized we were in the same city and decided to meet up. Thus many other opportunities came into existence, which have resulted in a book that Muslims and non-Muslims alike are eager to read. For instance, I introduced her to my friend Reverend Nell Green, a Christian whose narrative also came to be included in the anthology. This will be a breath of fresh air to readers who don’t want to read the same old story about veiling, but rather are looking for interesting, unique perspectives including one from a Christian pastor with years of experience living in Muslim countries.

The anthology is divided into sections. Part I, which includes my essay, is titled ‘Becoming Visible.’ In it, writers share how they first came to this piece of fabric that has become the stereotypical identity of Muslim women in western media. Some essays are deeply personal reflections on life. One essay is in the form of letters to strangers on the street (Dear White Guy on the Subway, for example). Perhaps the most striking essay is by Tanya Muneera Williams, who explains:

“I am a Muslim woman. I am a rapper. And I do wear hijab.”

Who doesn’t want to read the journey to hijab as experienced by a black Muslim woman who happens to be a rapper? It is a fascinating read which is sure to blow away stereotypes and educate readers in the same way Tanya has been doing with her music.

Part II is entitled ‘The Distribution of Normal.’ It includes narratives of non-Muslims, such as a white Christian teacher in the U.A.E. After her experiences with hijabi students, her return to the United States is a hilarious commentary on the state of dress here:

My time in the Muslim world has changed me fundamentally. I go home to North America and am shocked at how little clothes people have on. True, the environment shapes our attitudes and views and I have become more conservative as a result of being here. Yet, I am shocked at how shocked I am. Have “we” always walked around with so few garments? Did I used to walk around this way? Apparently yes, but I never thought of myself as inappropriately dressed before and now everywhere I look there are butt cracks, flabby arms, wrinkled and not-so-wrinkled cleavages, elephant knees, muffin tops, arm pit hairs, back hairs… I could go on. Oh please, someone put some clothes on all of these bodies!

Other sections of the book deal with other stories. There is an essay by a Hindu about the ghunghat, and one by a young man who falls for a hijabi girl only to be rejected. There are also essays that break one’s heart because they describe the pain women go through when they don’t wear the hijab. High school girls explain how they are teased by their more religious friends. Brides discuss how they are scolded by mothers-in-law. Confident Muslim women write about how the men and even the governments around them force them to cover themselves. Readers will see a full picture of the hijab with not only its beauty but also the ugliness that sometimes surrounds it. One writer explains is thus:

What I am trying to argue is that, at face value, the hijab is meaningless in terms of conveying the type of person the woman is. Unfortunately, my experience has taught me that judgments and conclusions are made about women based on the mere presence or absence of this otherwise neutral piece of headwear. It is often assumed that a veiled woman is a “good girl” — respectable and obedient to God and committed to her religion. Unveiled women, on the other hand, are suspect, their level of faith questioned by what some understand to be their disobedience of God’s orders for her to wear the hijab. This judgment of a book by its cover is both unfortunate and unfair.

“Mirror on the Veil” is a must-read, as well as a must-share. It will help readers learn more about the variety of thought and perspectives on the hijab. Buy it on Amazon.

2017

2,806 views

views

0

comments