The Frightening Effects of the NYPD’s ‘Mapping Muslims’ Program

The police department’s focus on piety as an indicator of a potential terrorist threat — one undercover officer went on a whitewater rafting trip with Muslim students and recorded how many times they prayed each day — had changed the practice of faith in the community.

By Henry Grabar

Between 2001 and 2011, in an expansive surveillance operation of Muslims in the New York region, the NYPD sent informants and undercover agents into cafes, mosques, restaurants, bookstores, clothing stores, salons and other businesses and institutions, assembling a collection of maps and guides whose level of mind-numbing detail — Are there newspapers available? Are antiques sold? Is the food Halal? — approaches that of a Lonely Planet guide to Islamic New York.

With the exception of widespread public outrage when the Associated Press exposed the program in a Pulitzer-winning investigation last year, the “human mapping program†of the NYPD Demographics Unit produced nothing: not one uncovered terrorism plot, not even a criminal lead.

In the city’s many Muslim communities, however, the NYPD has left a trail of mistrust and fear — fear of the police, yes, but also fear of political activism, freedom of speech, public religious observance and other basic constitutional rights. According to a report [PDF] released on Monday by CUNY-CLEAR, a law enforcement watchdog group, the surveillance program had touched nearly every aspect of public life for New York City Muslims.

“Surveillance sounds secret,†says Diala Shamas, a Liman Fellow at CUNY and a co-author of “Mapping Muslims: NYPD Spying and its Impact on American Muslims,†a joint product of CUNY-CLEAR, the Muslim American Civil Liberties Coalition, and the Asian American Legal Defense Fund, “but you’ll always have some kind of trickle down into the communities. It’s important to recognize that surveillance is strongly felt.â€

After interviewing dozens of students, businesspeople, religious leaders, and other community figures — as well as informants and police officials — the researchers found that few people were surprised when the extent of the NYPD program was revealed. For Muslims in New York City, it had become a fact of life.

One of the program’s more damaging consequences, the report finds, was its effect on freedom of speech. Public talk of politics and foreign affairs, from the mosque to the barber shop (especially discussion involving the tactics of the city’s police department) has now long been and is still seen as an invitation for scrutiny. A father urged his son not to speak with the Associated Press as the investigation was breaking, for fear of backlash. A cafe owner in Bay Ridge stopped tuning his television to Al-Jazeera, in an effort to avoid NYPD scrutiny. (The tactic was duly noted in an NYPD report on Egyptian cafes [PDF].)

The testimony underscores the extent to which young Muslims live in a different world from their friends. Muslim students think twice before using common avenues of expression: “I don’t talk about the NYPD on Facebook,†says one. Involvement in a Muslim Student Association at a local college was perceived as a virtual guarantee of surveillance, and proved to be so — the NYPD monitored over 30 Muslim student groups in the city alone, and kept watch on student groups as far away as Penn, Syracuse, and Yale. It wasn’t just political activism on campus that drew the department’s attention — a trip to play paintball became, in the eyes of the NYPD, “a militant paintball trip.â€

Perhaps the most pervasive effect of the ten-year surveillance program, whose details still remain largely unknown, was to sow suspicion in Muslim communities not only of the police but of neighbors. “You look at your closest friends,†said a local Sunday school teacher, “and ask: are they informants?â€

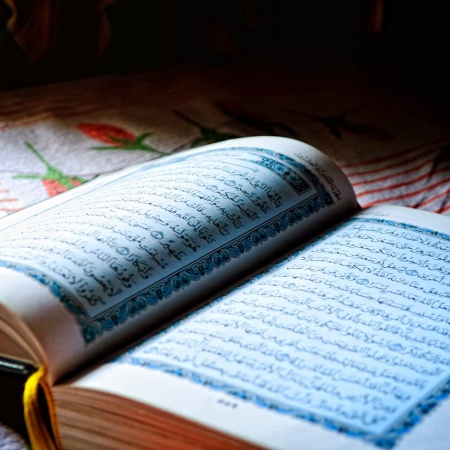

The police department’s focus on piety as an indicator of a potential terrorist threat — one undercover officer went on a whitewater rafting trip with Muslim students and recorded how many times they prayed each day — had changed the practice of faith in the community. “Attendance at mosque,†the authors write, “has become tantamount to placing oneself on law enforcement’s radar.â€

The presence of informants and spies at local mosques — “hot spots,†per the NYPD — was well-known, and splintered community discussions into smaller, private groups. (The presence of undercover agents in mosques has elsewhere led to some unbelievable stories.) “People come, pray, and leave,†said one imam. Certain ways of dressing had also become stigmatized. From parents to children, brothers to sisters, the warning was the same: if you dress Muslim, you are inviting police scrutiny.

The overriding theme that emerged across interviews, however, was an “entrenched, deep mistrust†of the NYPD, a divide that could, if other confrontations between minority groups and the police department are any guide, take a generation to repair.

15-12

2013

854 views

views

0

comments